Moral Injury

How Can We Help People Repair Moral Injuries?

The recommendations for self-help we provide to Veterans (see the Self-Help page) is predicated on the assumptions that the lasting biological, psychological, social, and spiritual impacts of high stakes moral violations are not principally caused by the way transgressive events are appraised or construed, and any purely psychological approach to healing and repairing will fall short because these approaches require moral injury to be caused by relativistic appraisals and constructions. The tacit implication of the purely psychological approach is that severe, high stakes deviations from what is right and just, and moral responsibility, are malleable. This moral relativism flies in the face of the biological imperative of reciprocal altruism and the transcendent and life-altering nature of most high magnitude, acute (e.g., opening a car door and killing a child on a bike; being brutally sexually assaulted by peers aboard a Navy ship) or chronic moral injuries (e.g., countless instances of degrading and cruel treatment by an enemy).

As is the case with high magnitude memories, memories of morally injurious experiences cannot be extinguished or lessened by reframing. The aim is to make those memories and the implication of those experiences compete with countering memories and experiences, inhibiting the accessibility of the immutable existential reality of moral harm. Consequently, at the end of the day, helping people with clinically impairing moral injury entails helping them do things and to avail themselves of things in the world they inhabit that are corrective learning experiences with respect to judgments about how good or bad they or people are or can be. This requires action in service of shifting the balance of how good or bad someone is or how good or bad the world is.

Considering what is likely to be lost by various morally injurious experiences may help both clinicians (to conceptualize their cases and plan treatment) and clinical researchers (to think of testable predictions and approaches to helping people with moral injury). In contrast to threat-based stressors, high stakes morally injurious experiences can alter the relationships and activities that sustain our identity, our sense of connection to people, families, and communities, and individual and collective humanity.

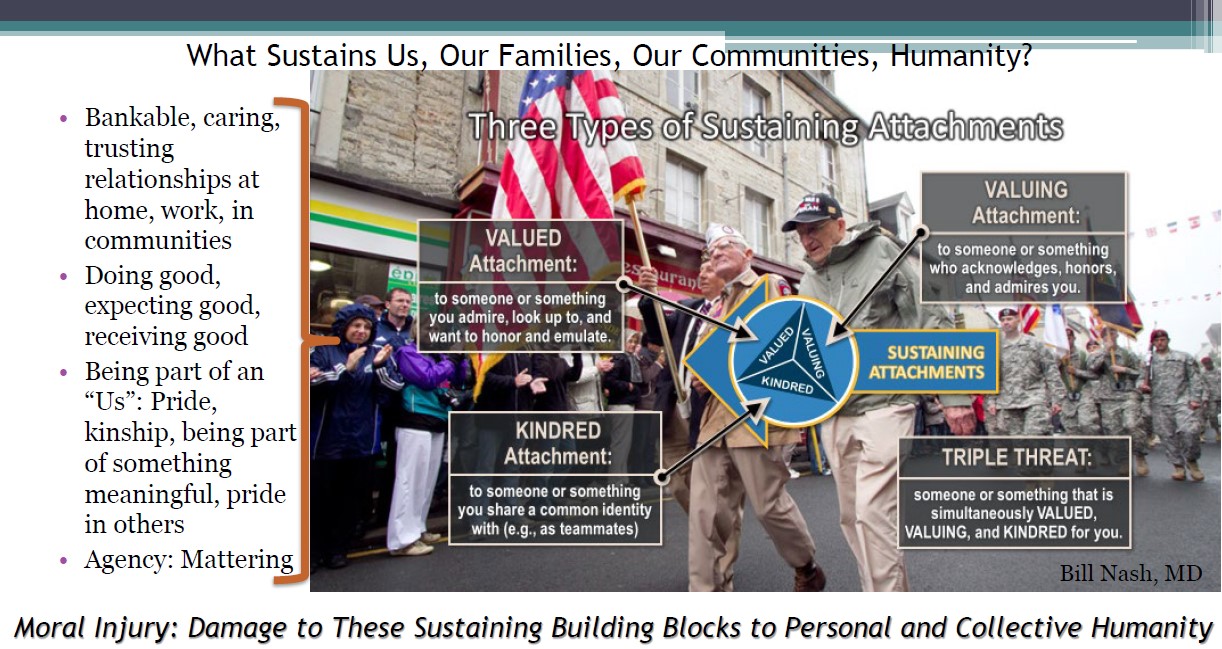

The Figure below depicts three types of sustaining attachments generated by Bill Nash, MD, a thought leader on moral injury, each of which can be altered and lost from moral injury. These are: (1) valuing others; (2) being valued; and (3) being part of a valued kindred group.

Moral injury damages these attachments, which are sources of comfort, safety, trust, love, virtuous behaviors, pride, meaning, and relational agency. Healing and repairing moral injury require rebuilding or establishing the building blocks to personal and collective humanity. Existing mental and behavioral health treatments such as: (1) medication designed to address dysphoria and anhedonia or anxiety; (2) cognitive therapy strategies designed to help one learn that some appraisals are malleable and can affect mood and to change one’s broad beliefs; (3) exposure therapy strategies designed to help one approach dreaded internal experiences and contexts and to enhance agency, behavioral strategies that address withdrawal and poor self-care (etc.); and (4) spiritual counseling, can all be used to help people with moral injury. Arguably, when these work, they help people be open to doing reparative things or to availing themselves of reparative attachments in their world.

Treatment Planning

The treatment planning issues that are germane to this framework are:

- Does the person have a history of virtuous behaviors? Were they part of a group or something that they valued and were they a valuable member of the group? Were people a source of comfort and care? Were people trusting and trustworthy?

- What is the quality of the current social, work, and community context? Is there at least one person that is loving, compassionate, and trustworthy? Is there an example of such a person historically? Are there current sources of reparative good attachments?

- In the case of personal transgressions, has the person been contrite and taken responsibility? In the case of being the victim of others’ transgressive acts, has there been any truth-telling and attempt at repair and reconciliation?

- Is the person currently excluded, vilified, excluded (cancelled) by others? Or, is the person cancelling others or groups of others?

- To what extent has faith, loss of faith, spirituality or the loss of spirituality caused various functional impairments related to moral injury symptoms? To what extent would the individual want to or consider being involved in faith / spiritual communities or rituals and habits?

Treatment Approaches

For a review of psychotherapies that may be helpful in treating moral injury, see the link below:

For a summary of the potential role of chaplains in treating moral injury, see the link below:

For self-help guidance for Veterans and families, see the Self-Help page.