Moral Injury

What Are the Symptoms of Moral Injury?

The Moral Injury Outcome Scale Consortium led by Brett Litz was comprised of researchers and clinicians working with Service Members and Veterans in the US, the UK, Australia, Israel, and Canada. The Consortium used theory and qualitative data to operationalize the domains of impact from exposure to PMIEs and to develop a psychometrically sound measure of MI as an outcome that can be used in research and clinical care. The scale development process had three phases. Phase I entailed content generation and the creation of the initial measure. This effort included qualitative interviews with Service Members and Veterans regarding their exposure to PMIEs and, if so, about the lasting and current impact of the worst and most currently distressing PMIE. Qualitative data reduction was used to extract domains of impact and components within domains that do not overlap with PTSD or depression from transcribed interviews. The Consortium also interviewed, clinicians and chaplains about their observations about the symptoms of MI. Phase II entailed scale refinement and reliability testing. Phase III consisted of testing the convergent and discriminant validity of the final scale called the Moral Injury Outcome Scale (MIOS, which is described in the assessment section).

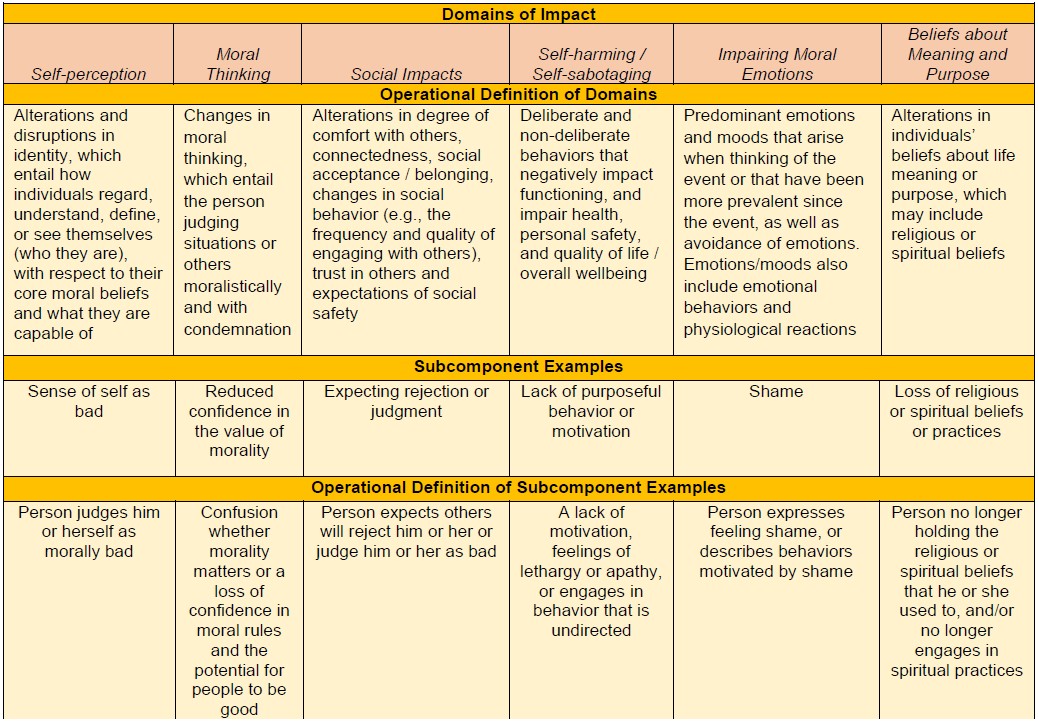

This research revealed that the aftermath of exposure to PMIEs entails domains of impact and symptoms that do and do not overlap with PTSD or depression symptoms. Core symptoms of MI include alterations in identity (self-perception) and the way others are construed; judgmental attitudes; alterations in belongingness, worthiness, and comfort with others; self-harming behaviors; predominant moral emotions and moods, and changes in faith or spirituality. The following are the domains of impact, definitions of the domains, and examples of subcomponents with domains (and their definitions) that were used to create the Moral Injury Outcome Scale and comprise the MI syndrome:

A Continuum Model of Moral Stressors and Responses

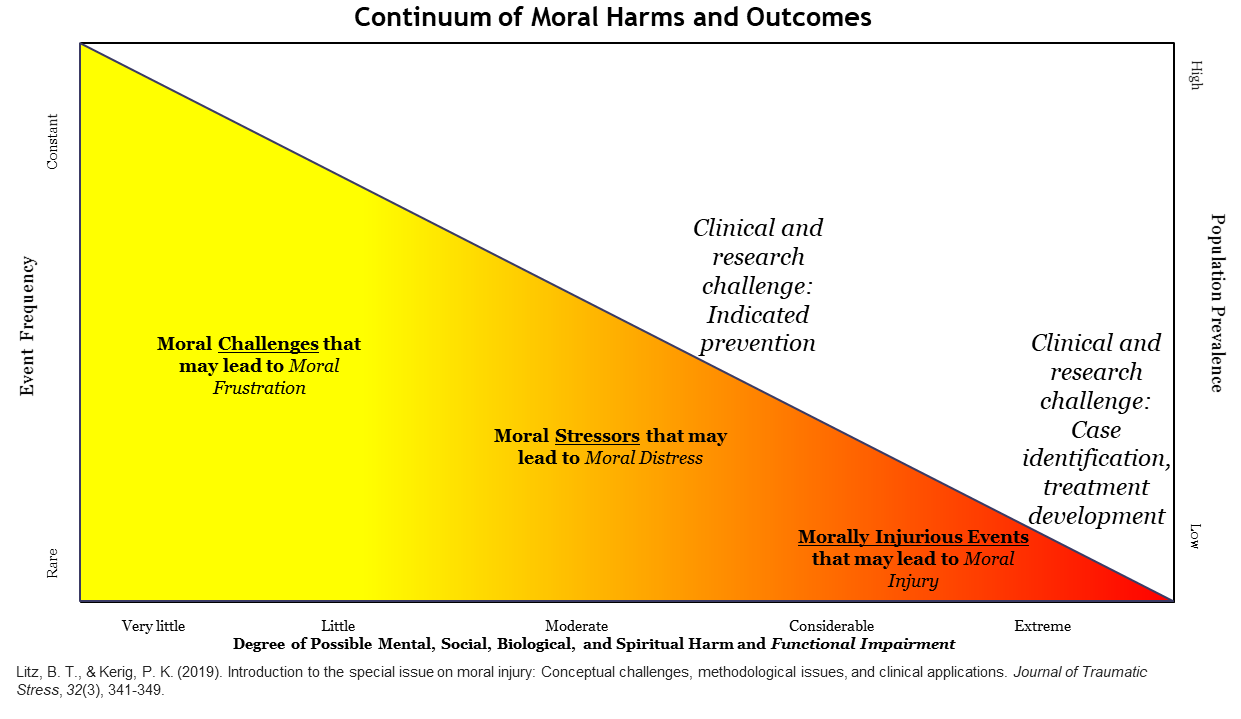

The Figure below depicts a continuum of morally relevant life experiences and corresponding responses, with varying magnitudes and impacts (Litz & Kerig, 2019). Because of the centrality of moral judgments and decision-making in human life, experiences that violate a person’s moral beliefs will elicit biological, social, and psychological reactions. The magnitude and impact of responses are shaped by culture and the person, and by the nature of the moral conflict. Experiences that are ongoing or have no immediate self-relevance are moral challenges that may lead to moral frustration. A good example of this are concerns about climate change. In contrast, events that are self-referential (e.g., when one is a moral agent or is directly impacted by others’ transgressive behaviors) are moral stressors that may result in moral distress. The most prominent features of moral distress are moral emotions (anger or shame) that predominate experience. Moral distress is stressful and impairing but not significantly functionally impairing. Examples of moral stressors include behaving hurtfully to someone you love or being subject to such transgressions. People may have intrusive thoughts about moral stressors, but they are not disabled by them nor does the experience define them. Moral stressors occur less frequently than moral challenges and more is at stake with these kinds of events. Moral stressors are less likely to involve grave threats to personal integrity or loss of life in comparison to PMIEs. PMIEs are the least frequent and are abnormal, but they are the most potentially functionally impactful, resulting in the outcome of MI.

People who struggle with moral distress do not necessarily believe that they or others are defined by the experience. By contrast, people who struggle with MI make enduring attributions about themselves or others (Litz et al., 2009). In the context of moral distress from personal acts, individuals may feel guilt and do something to mend the violation. In the case of self-based MI, shame predominates, and the act comes to define one’s identity and cannot be readily repaired by making amends. In the case of other-caused moral distress, one may be periodically angry, wanting things to change, but they are able to function if things do not change. In other-caused MI, anger predominates, and it is impossible to reconcile the experience without a change in others’ behavior. In the context of perpetration-based MI, the attribution that must be reconciled in some way is that “I am bad.” In the context of being subjected to someone else’s egregious moral violation, the attribution that must be reconciled is “that person and most others are bad.” Epidemiologically, moral challenges are part of everyday life. By contrast, moral stressors are acute insults that are not common but are more common than PMIEs. Accordingly, the prevalence of MI as an outcome is likely low, even in risky contexts and occupations. Moral distress is normal, and the expectation is for complete recovery with no lasting harm. We can reconcile questions about where moral struggles lie on the continuum of normality by placing MI into the realm of abnormality and framing the outcome as clinically concerning because of the severity of functional impact.

People who struggle with moral distress do not necessarily believe that they or others are defined by the experience. By contrast, people who struggle with MI make enduring attributions about themselves or others (Litz et al., 2009). In the context of moral distress from personal acts, individuals may feel guilt and do something to mend the violation. In the case of self-based MI, shame predominates, and the act comes to define one’s identity and cannot be readily repaired by making amends. In the case of other-caused moral distress, one may be periodically angry, wanting things to change, but they are able to function if things do not change. In other-caused MI, anger predominates, and it is impossible to reconcile the experience without a change in others’ behavior. In the context of perpetration-based MI, the attribution that must be reconciled in some way is that “I am bad.” In the context of being subjected to someone else’s egregious moral violation, the attribution that must be reconciled is “that person and most others are bad.”

People who struggle with moral distress do not necessarily believe that they or others are defined by the experience. By contrast, people who struggle with MI make enduring attributions about themselves or others (Litz et al., 2009). In the context of moral distress from personal acts, individuals may feel guilt and do something to mend the violation. In the case of self-based MI, shame predominates, and the act comes to define one’s identity and cannot be readily repaired by making amends. In the case of other-caused moral distress, one may be periodically angry, wanting things to change, but they are able to function if things do not change. In other-caused MI, anger predominates, and it is impossible to reconcile the experience without a change in others’ behavior. In the context of perpetration-based MI, the attribution that must be reconciled in some way is that “I am bad.” In the context of being subjected to someone else’s egregious moral violation, the attribution that must be reconciled is “that person and most others are bad.”

Epidemiologically, moral challenges are part of everyday life. By contrast, moral stressors are acute insults that are not common but are more common than PMIEs. Accordingly, the prevalence of MI as an outcome is likely low, even in risky contexts and occupations. Moral distress is normal, and the expectation is for complete recovery with no lasting harm. We can reconcile questions about where moral struggles lie on the continuum of normality by placing MI into the realm of abnormality and framing the outcome as clinically concerning because of the severity of functional impact.

Next: Treating Moral Injury